Is It My Thyroid? How To Comprehensively Evaluate Thyroid Health

It seems that every day, week, or month has some association to it. National Cupcake Day or National Ride Your Bike To Work Week. But this highlighted week is something I can finally get behind. May 12th-18th is National Women’s Health Week and there is nothing I can think of that has a greater impact on women’s health than thyroid health. Thyroid conditions more commonly affect women compared to men yet it is woefully under-diagnosed.

Your thyroid is an endocrine gland (meaning it makes hormones) that sits at the base of your neck and can impact metabolism, mood, other hormones, skin health, menstrual cycle, digestion, and much more!

Since it affects almost every system in your body, when your thyroid gland is not working properly, the symptoms can vary greatly from person to person and sometimes can even mimic other diseases. Depression? Constipation? Irregular menses? Joint pain? Difficulty losing weight? Maybe it’s your thyroid.

There is a 6-page long list of all the types of issues your thyroid can manifest so suffice it to say, it is one thing that I most commonly evaluate for in the majority of my patients.

There are two types of thyroid dysfunction: hyperthyroid, which is an over production of thyroid hormones, and hypothyroid, which is an underproduction of thyroid hormones. Hypothyroidism makes up at least 80% of thyroid issues and affects at least one in ten women, which is why it’s crucial to think about when we talk about women’s health issues. Due to the prevalence of hypothyroidism vs hyperthyroidism, the rest of this article will focus on hypothyroidism.

If, like a lot of women, you have asked your doctor to evaluate your thyroid health, they most likely have checked TSH, which is thyroid stimulating hormone. Although this test may give you a clue to what’s going on with your thyroid, it doesn’t actually tell you what your thyroid is doing.

To better understand the right type of tests to check your thyroid health, let’s talk about all the hormones involved with your thyroid.

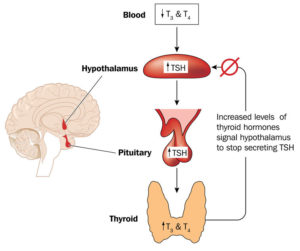

In order for your body to produce thyroid hormone, the process starts in your brain. Your hypothalamus produces TRH (thyrotropin-releasing hormone). TRH then stimulates your pituitary (still in your brain) to produce and release thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

TSH leaves your brain via your blood and tells your thyroid gland to release your actual thyroid hormones. You have two main thyroid hormones: triiodothyronine (known as T3) and thyroxine (known as T4). Both of these hormones are produced by your thyroid gland but T4 is made in higher amounts compared to T3. However, T3 is the more active form of your thyroid hormones and will be converted from T4 in the rest of your body, particularly your liver.

Since T3 is essentially more potent than T4, if T3 is low but your T4 is normal, you will be more likely symptomatic.

As I mentioned, the mostly commonly (and usually only) run test to evaluate for thyroid is TSH. The idea behind testing TSH is that if your levels of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) are too high, it will lower your TSH because you don’t need to keep making thyroid hormones. So if someone has a low TSH, they may be hyperthyroid.

On the other hand, if your thyroid hormones are too low, TSH will increase. So if someone has an elevated TSH, we would consider that to be hypothyroid.

If you’re still confused, watch the video!

The problem with only testing TSH is that doctors assume that the thyroid and brain are following this pattern. But they are not evaluating what your thyroid gland is actually producing. I have seen time and time again where TSH comes back as “normal” but the thyroid hormones themselves are being underproduced.

Once in a while, your doctor may throw in a total T4 in addition to testing TSH. But this again, is problematic.

As we discussed, T3 is the more potent thyroid hormone compared to T4 so if your T4 is normal but you still have thyroid symptoms, you may not be converting enough to T3.

It is also important to note, we want to check the free versions of these hormones (so free T3 and free T4, sometimes abbreviated as fT3 or fT4) and not the total. Free hormones are what are available for your body to use as they are not bound to a protein. So you may have normal total levels of the thyroid hormones but the free forms are low and causing symptoms.

An easier way to think of this is if you had money deposited into a 401K and your general checking account. The money in your checking is available to use immediately but if that account becomes low, you can’t just easily take money from your 401K. That money is unavailable. Or in the case of your thyroid, you may have adequate amounts of T3 or T4 but they are not available to be utilized.

Now the other issue I commonly see beyond not thoroughly testing the thyroid hormones (and there’s still more to check for that we’ll discuss) is to only look at the conventional ranges.

When you think about lab testing, the ranges that are used are an average of the population. I’m sure you’d agree that our average population is not healthy. Diabetes and pre-diabetes affects over 100 million people in the United States and heart disease is another 28 million.

So if you’re told your thyroid results are “normal”, consider what normal actually means. Some women can have subclinical hypothyroidism meaning they have thyroid symptoms but their labs are normal. This is why I always look for optimal levels for thyroid tests.

Another thyroid hormone test that I’ve started running more frequently is rT3, or reverse T3. This is essentially your storage form of T3 so if this is elevated, your body may be storing more of your T3 than you want it to, again causing symptoms. So similar to total versus free hormones, the T3 is not available to be used.

Lastly, another component to consider is to evaluate for autoimmune thyroid conditions. Hashimoto’s is an autoimmune condition that is the most common form of hypothyroidism.

It’s good to get tested and evaluate for this as most people with hypothyroidism have Hashimoto’s. In fact, I’ve had several patients that have been diagnosed as hypothyroid for years but were never tested for antibodies. When we tested them, they were positive for Hashimoto’s.

I can only speculate but I assume the reason Hashimoto’s is not commonly tested for those with hypothyroidism is because it doesn’t change their conventional treatment plan. However, from a naturopathic and holistic perspective, it changes a lot! Treating an autoimmune condition can look quite different than treating general dysfunction.

In addition, I have even had some patients have optimal thyroid hormones but were positive for Hashimoto’s. So anytime I evaluate for thyroid disease, I also check for Hashimoto’s. Again, this is not standard conventional practice but valuable information if you want to treat the underlying root cause.

When we evaluate for Hashimoto’s, we’re testing someone’s antibodies. Antibodies are essentially markers that will bind to a cell and mark it for destruction. They are a part of your immune system, communicating to other parts of your immune system, “This cell is foreign and it’s not supposed to be here so get rid of it!”

Obviously, this system works great against bacteria, viruses, etc. But with any type of autoimmune condition, such as Hashimoto’s, your immune system is confused and targeting the wrong cells.

The antibodies I commonly test for to evaluate for Hashimoto’s is called TPO (thyroid peroxidase) antibodies and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies. These can be quite elevated with Hashimoto’s.

To sum it up, a thorough thyroid panel would include testing TSH, free T3 and free T4, reverse T3, and TPO and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies. So if you have the sneaking suspicion that your thyroid may be to blame for some of your symptoms and all that’s been tested is TSH and maybe total T4, you should consider asking your doctor for a more thorough panel. This may just be that piece of the puzzle that’s been missing all along!

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post